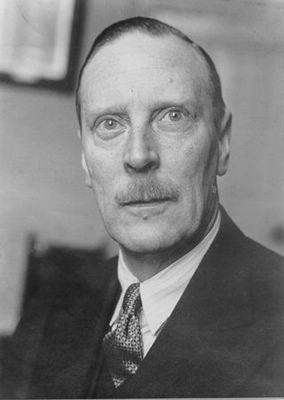

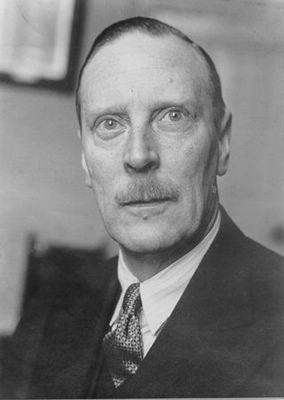

Sir Alexander was educated at Malvern College and Pembroke College, Cambridge. He served with the Coldstream Guards in the First World War, was awarded the Military Cross and mentioned in despatches.

He then entered the Civil Service and served in the Colonial Office from 1922 to 1928, during which time he visited Ceylon.

Sir Alexander then moved to the Dominions Office and was a member of the United Kingdom Delegation to League of Nations Assembly, 1929, 1930 and 1931. He was Secretary to the Newfoundland Royal Commission and visited Canada and Newfoundland in 1933. He paid a further visit to Newfoundland in 1938.

In 1939 Sir Alexander was appointed Deputy High Commissioner for the United Kingdom in the Union of South Africa.

In 1942 he was appointed Assistant Under-Secretary of State for Dominion Affairs, when he again visited Canada and Newfoundland, with the then Deputy Prime Minister, Mr. Atlee.

In 1946 he was appointed High Commissioner for the United Kingdom in Canada, and served in that capacity until 1952. He was greatly involved in the diplomatic processes that resulted in Newfoundland joining Canada, as

the tenth Province.

On November 25th, 1948, Sir Alexander gave an address to the

Empire Club in Toronto, closing with remarks that ring as true today.

One of the things that gives me greatest encouragement at this time is the way in which good comes out of evil. And it is coming out. We are seeing formed before our eyes a great new unity of purpose, a new brotherhood, if you like, which sees itself manifested not only in the Commonwealth--and our relations in the Commonwealth have never been closer than today--but which embraces also that great neighbour to the south of us. It reminds me of the words of Mr. Winston Churchill, in one of his great speeches in the war. You will remember his remarking of the United States how increasingly we were mixed up together in our affairs, "It is a process", he said, "which, like the Mississippi, just keeps rolling on and nothing in this world is going to stop it". I think in that great unity and closer brotherhood lies our greatest safeguard for maintaining peace in the world, and our greatest guarantee we shall together enter that new age to which I have referred.

He received an honourary Doctor of Laws degree in 1951, at convocation of the

University of British Columbia, and it was noted:

In a tense and troubled period Sir Alexander has brought to the duties of a most responsible position a sensitive and virile appreciation of those traditions of public service, in peace and in war, which we have inherited from the United Kingdom and which we are proud to share with the British Commonwealth of Nations, with the United States of America and with all nations that cherish freedom. I now present to you, Sir, for the degree of Doctor of Laws, honoris causa, a man who as soldier, public servant, and statesman has ordered his life in the spirit of those whose devotion we honour today. Sir Peter Alexander Clutterbuck.

A career diplomat, Sir Alexander went on to serve as the British Ambassador to Ireland from 1955-1959. At that time he was painted by Henry R. Craig in his work titled

The Dublin Drawing Room.